Full Keel vs Fin Keel

How Lift, Drag, and Leeway are Affected

In this article, I’ll address the question of how a fin keel has LESS leeway than a full keel. At first sight, everything seems counterintuitive – surely a full keel has more resistant to being pushed sideways through the water and thus less leeway!

The answer lies with hydrodynamics, but first, I’ll start with aerodynamics, just because we all watch aeroplanes every day, but none of us stick our head underwater and watch a keel go ripping past while holding our breath.

Keep in mind throughout the article that I’m not ragging on full keels (they DEFINITELY have advantages – especially in cruising), I’m just explaining why a fin keel has less leeway.

###

In Enginering school at the University of Auckland, New Zealand, our aerodynamics professor gave us a practical assignment towards the end of the semester – create a glider using 1 square meter of paper, a stick of balsa wood, and a 100-gram rod of steel. He wanted to see how much we’d absorbed in the class. The winner was to be the one who created the glider that stayed aloft for the longest time when pushed off the second story inside the gymnasium.

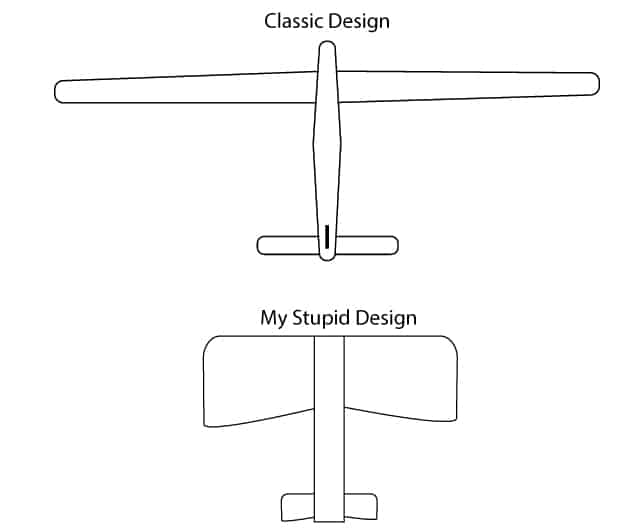

Being the renegade disruptor I am, I created a glider much the shape of a hang glider. I even built a little active sling device for the 100-gram weight to simulate a human steering the glider. I was opting for stability. Those who listened in the class built a glider that maximised the aspect ratio of the wings given the 1 sq meter of paper allowed. Aspect ratio is the ratio of length to area. Thus, a long wing has a higher aspect ratio than a short fat wing.

Mine pretty much went straight to the gym floor, while the listeners and followers of pure theory and the mathematical equations we’d learned had quite success.

The lesson was to drive home how aspect ratio has less drag. Less drag means more lift.

How does a higher aspect ratio wing create more lift over a lower aspect ratio wing for the same area of wing?

Since both low and high aspect ratio wings have the same amount of area presented to the air molecules, and lift is proportional to the velocity squared times the area, then the question remains.

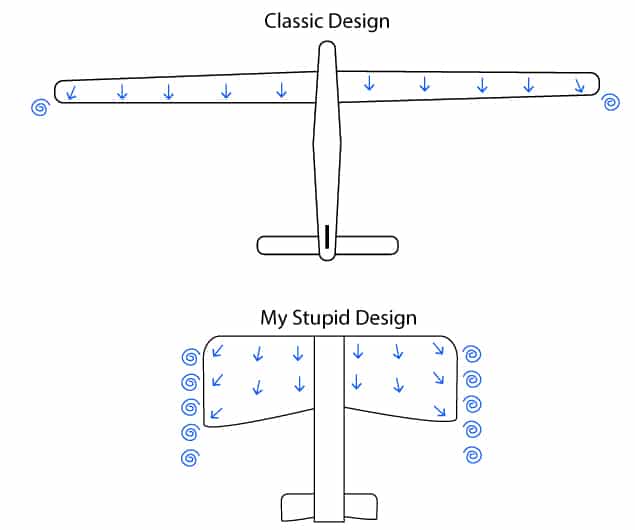

The answer lies purely with the energy lost in the vortices coming off the edge of a wing. A fat wing, as above, loses more energy to the vortices than the high aspect ratio glider.

To visualize a vortex of the end of a wind, here is a great photo showing this phenomenon

Energy spent on generating vortices is energy lost as lift. Since the vortex comes off the edge of the wing, reducing the size of the wing edge i.e. a high aspect ratio, helps increase the efficiency of the wing.

Let’s shift to sailboats because a keel is NOT a WING.

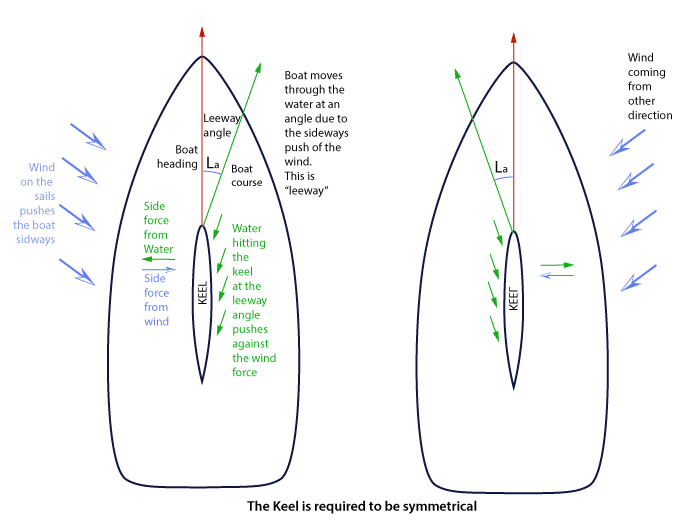

A wing is asymmetrical with the curve on top to take advantage of the lift from the airfoil shape. However, a keel on a sailboat must be symmetrical because the water can impinge on either side of a keel, depending on what tack the boat is on.

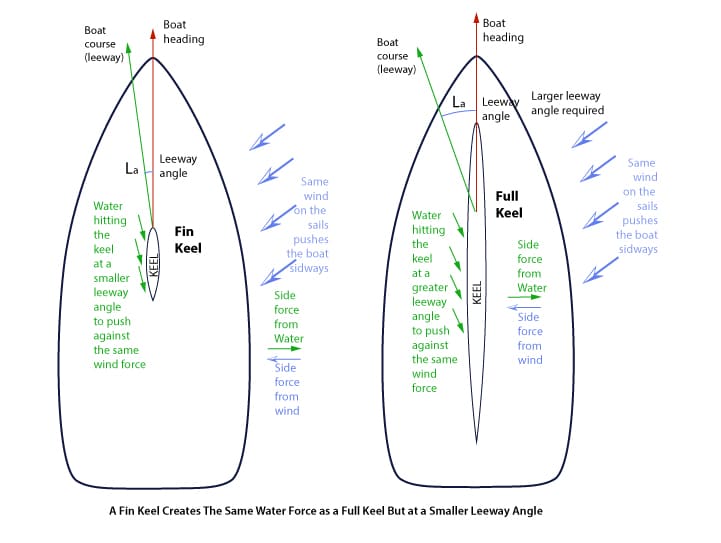

Notice that the water impinging on the keel creates a force on the keel in the direction opposite to the sideways force created by the wind. Some call this water force “lift”. But it is not lift like in an airplane sense because an airplane wing makes the plane go up. In a sailboat sense, the water force balances the sails’ sideways leeway force – technically it is lift but calling it that may make the thought that the symmetrical keel can make the boat climb up wind – “windwardway”. It can’t – there must be leeway – sideways acting water must impinge on the keel – imagine if the water came from directly ahead, then there would be no water sideways force on the keel. So forget the notion of “lift” in a windward manner. A sailboat, by very definition, must have leeway to balance the side force of the wind. So let’s call this force “water force on the keel” instead of “lift”.

So the job of the keel is to take the water hitting it at a sideways component and use that to push back against the wind (which is pushing the boat sideways). If not for the keel, the boat would just slip sideways across the water due to the wind pushing it. Whoever invented keels – brilliant!

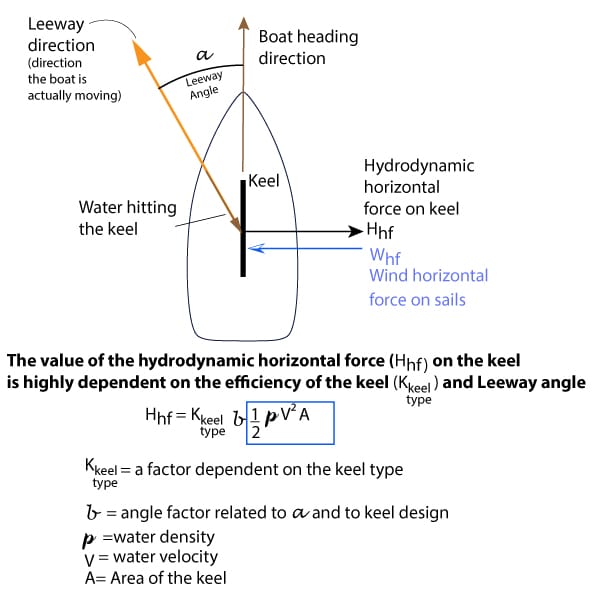

For now, remember this – you have to have leeway for a keel to work. But how much leeway angle of water pushing on the keel do you need? The factors that are involved are water density (fixed), velocity of the water impinging on the keel, the area of the keel, the angle at which the water impinges on the keel, and a factor “K” related to keel design and aspect ratio.

The following shows these factors at work .

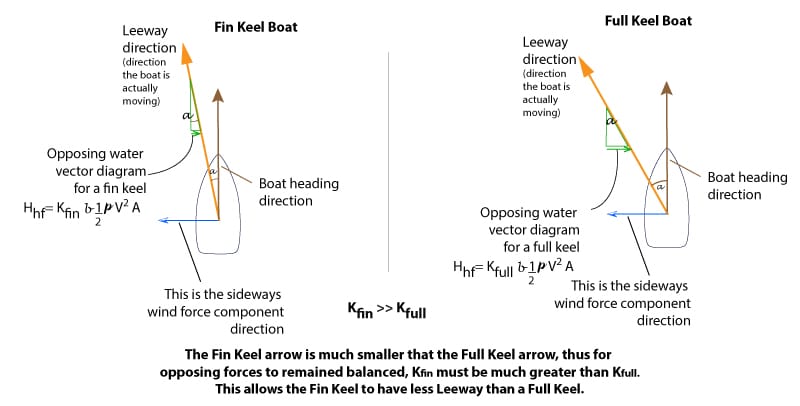

Many of us are used to the classic ½ ρ V² × Area formula for calculating force (that’s the blue square above). But once we start dealing with a 3-dimensional keel in real water — things like vortices, keel shape, and the impinging angle of the flow — the “simple” force formula needs a couple of add-ons. In the diagram above I’ve shown those as an efficiency term K (keel type) and an angle term b. Those add-ons are tightly linked to keel design, and they’re what really determine how efficient the keel is at pushing back against the wind.

Even if you’re not familiar with the formula, it honestly doesn’t matter. The main takeaway is this: the sideways force from the water on the keel (the force that resists the wind’s sideways push) depends heavily on water density, water speed hitting the keel, keel area, the leeway/impinging angle, and—most importantly—the keel’s design and efficiency.

Now here’s where people get tripped up (including me the first time I tried to sketch this). If we apply the basic “Newtonian” idea, we’d say the force is proportional to ½ ρ V² × Area, and it increases with the angle the water hits the keel. So you might ask: if a fin keel had the same area as a full keel, shouldn’t the force be the same? And since full keels often have more surface area than fin keels (even if fin keels are usually deeper), it can start to look like the full keel ought to do better, not worse. And if the fin keel actually sails with a smaller leeway angle, how can it possibly generate more opposing force?

This is where the “simple” law runs out of road. That basic force idea is effectively a 2-dimensional model. As soon as we step into the real 3-D world of keels — aspect ratio, tip vortices, and the energy lost into swirling water — we need an extra factor in the formula to account for efficiency. That’s what the K factor is doing here. It’s the “3-D correction” that captures the keel’s design, how much vortex loss it creates, and how effectively it turns leeway into useful sideways force.

Now let’s talk fin keels versus full boat length keels.

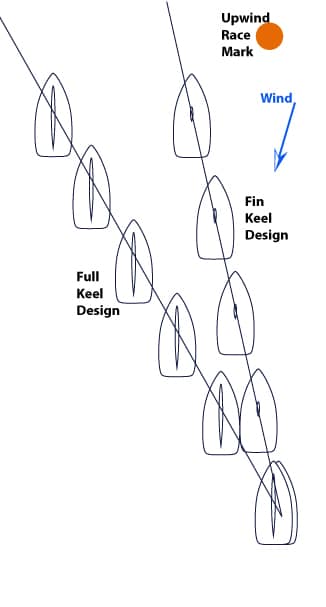

Ask a racer, and they will always opt for a fin keel over a full-length keel. The fin keel boat has less leeway and will crush a full keel boat in an upwind leg. And they are correct.

A fin keel is simply more efficient at pushing back against the wind. More efficient means it needs less of a leeway angle to push back against the wind. Thus, the racer heads at a better angle to the wind.

So why do fin keels have more push-back force against the wind than full keels? It seems impossible!

The diagram below shows the fin keel operating with less leeway. And since the leeway angle is smaller for the water to put force on the keel – the only variable to make the fin keel have equal force to the wind at a smaller angle is that the K factor for the fin keel must be much much larger than the K factor for the full keel.

The answer lies that the Newtonian law only assumes a 2-dimensional model. What happens is that there is a difference in the efficiency of the water impinging on the keel for the two different keels.

Thus, the reason for the vortex discussion above.

View the two animations below.

The first is a fin keel showing little vortex spinning of the bottom of the keel.

This is a full keel showing the large amount of vortices and thus the inherent inefficiency.

So this is where the K factor comes into play in the formula. K for a fin keel is much much larger than K for a full keel due to the large effect of the vortices associated with a long bottom edge. This means that the only other variable left to make up for a smaller K is the leeway angle. Thus, the leeway angle for a full keel must be larger for a full keel than a fin keel – and this is exactly why my airplane in the gym 40 years ago glided straight down to a C grade for the assignment, while my classmates who listened to the theory and the mathematics held aloft with an A grade.

The Takeaway you can share over a beer

So next time someone says to you that keels work to slow the sideways slip purely because they provide a big resistance to the water, you can now say back something like this:

“A keel isn’t just there to stop the boat from sliding sideways — it’s actually using the water to push back against the wind. As the boat slips a little sideways, water hits the keel at an angle, and the keel deflects that flow, which creates a sideways push in the opposite direction. A fin keel does this really efficiently, so most of the water flow turns into useful push instead of wasted turbulence. A full keel still does the same job, but it drags a lot more swirling water along with it, which wastes energy. That’s why fin-keel boats don’t slide as much and go faster upwind — they’re just better at turning water flow into useful force instead of turbulence”.

###

But this is not the full story – there are other causal effects such as drag, which further slow a full keel.

But don’t get down on full keels, they do have advantages, however. So don’t make up your mind yet about which keel to have. Standby for more articles on this topic.