The Rio Dulce, a King Tide, and Why My Brain Wouldn’t Shut Up

How Mast Spreaders Are Magic

Why you should read this: – a study of what danger you put your rig into when heeling the boat over using a mast head pull from a rescue boat.

by Grant Headifen

Sailor

Engineer

Story Teller

And a Sucker for a Good Adventure

There are moments in sailing where you think you’re executing a solid plan… and then nature quietly leans over and says, “Cute idea. Let’s add silt.”

Our moment came at the entrance to the Rio Dulce in Guatemala. It is a known tricky entrance where knowledge of how king tides work and getting the offset in your depth meter exact. The sand/silt bar at the buga (“mouth” in local Garifuna language) of the river is REALLY shallow. Yes – inches do matter!

We had timed it perfectly. Highest of high tides. Best possible window. The one shot that mattered—because if we didn’t get in now, we’d be waiting until the next king tide.

The plan was sound.

What we hadn’t fully accounted for was that it was rainy season. Which meant the river had been busy doing what rivers love to do: dumping extra silt exactly where you don’t want it.

So there we were, easing our 63-foot Cheoy Lee motorsailer (50 tons, long keel, 6½ feet of draft) across the bar exactly through the reported deepest part of the channel … when progress quietly stopped.

No bang. No drama. Just drag.

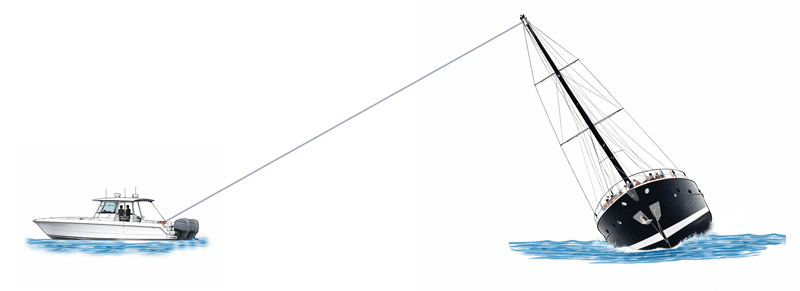

That’s when the local skipper arrived with two boats and a plan that instantly raised eyebrows:

One boat would tow us forward. The other would take a line from the masthead and pull sideways to heel the boat.

The captain and his wife were… unconvinced.

Pull. On. The masthead. Really?

Trying to sound calm (and maybe wiser than I felt), I said:

“Well… the wind heels the boat all the time.”

That sentence would cost me the rest of the afternoon.

Heeling the Boat Over by a Mast Head Pull by a Powerboat

We Got Free. The Engineering Brain Got Stuck.

The maneuver worked. Smoothly. Slowly. No shock loads. Minimal waves. The boat heeled—somewhere around 18 degrees—just enough to reduce draft and let the keel slide through the silt.

Rig still standing. No strange noises. No mast lying across the deck like a fallen tree.

But once we were safely tied up in the Rio Dulce, my brain refused to accept the happy ending without an investigation.

How close were we? Had we been flirting with the limits of our 7/16″ standing rigging? Was my casual “the wind does this all the time” actually true… or just something sailors say to feel better?

Leverage: Why Masthead Pulls Feel Spicier Than Wind

Here’s the first thing that matters.

A sideways pull at the masthead—about 75 feet above the water—uses leverage instead of brute force. Like a screw drive on a paint can lid. The higher the mast head the less force required to heel the boat.

In our case, we calculated (after) that it took roughly 3,000 pounds of sideways force at the masthead to produce a required heeling moment of 225,000 ft-lb to get the boat to heel over 18 degrees.

To get the same heel angle from wind, the wind has to push on the sails at their center of effort, which is much lower—around 28–30 feet above the water.

Lower lever arm means more force required.

That means the wind needs roughly 7,500–8,000 pounds of sideways aerodynamic force to create the same 18° of heel.

Same heel. Very different forces. And a mast head pull with a huge point load at the top sheaves versus a distributed load by the wind felt highly unnatural and spicey to say the least.

And keep in mind that none of this real thinking was going on during the decision to hook up the mast head pull. The decision was more driven by the tide was about to go down and something needed to happen quickly. If we weren’t getting through on this high tide, it certainly would not happen on the next.

The only thought was – is the mast head pull the same as wind or not and does the mast head pull create untenable forces? Who could say in the moment? The owners had horrid visions of living on the sandbar for weeks with a horizontal mast.

So lets take a look at the forces. If the powerboat was pulling 3000 lbs sideways at the top of the mast how does that translate into shroud force?

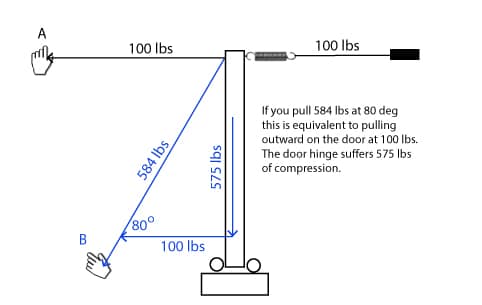

The “Angle of the Dangle” (a Door, a Spring, and a Mast)

This is where geometry sneaks in and multiplies things.

Imagine a door that swings both ways. On one side of the door, someone attaches a spring. On the other side, you’ve got a rope.

If you pull the rope perpendicular to the door, you’re pulling straight against the spring. Simple.

But now pull the rope from an angle closer to the hinges.

To get the same sideways force against the spring, you now have to pull harder. Where does the extra force go?

Into the hinges – compressing the door.

Now rotate that whole setup vertically so the hinges are on the bottom.

Congratulations:

- The door is now your mast

- The rope is your shroud

- The sideways force is heeling

- The extra force from the bad angle becomes mast compression

That extra force is the multiplier.

Bad angle? Big multiplier.

That’s the “angle of the dangle” or really the angle of the shrouds to the mast. That angle creates the multiplier of the 3000 lb force. But how much? And is it more than the 7/16 shroud strength or even the strength of the connection points or the chain plate. The chain plate is the plate embedded into the hull of the boat that attaches to the shrouds to provide a strong pull point for the shrouds.

Top Down View of a Swing Door on Hinges

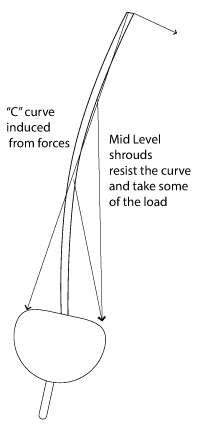

The Forces Create a Propensity for the Mast To Bend

Why Spreaders Quietly Save the Day

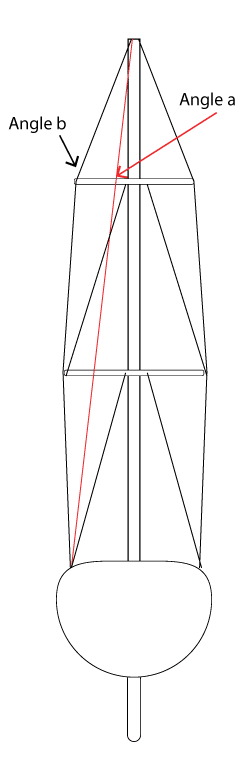

Our rig has double spreaders:

- Lower spreaders (~6 ft) at about 1/3 mast height

- Upper spreaders (~4 ft) at about 2/3 mast height

Spreaders improve the angle between the shrouds and the mast. From the image, you can see that angle b is much larger than angle a. That does two huge things:

- It reduces the tension multiplier (less force needed to get sideways support)

- It forces load sharing into the intermediate and lower shrouds

Instead of one tall, skinny triangle of doom, the rig breaks the load into multiple shorter, stronger triangles.

And here’s the sneaky part…

Even the “Wrong Side” Shrouds Help

As the mast is pulled sideways, it doesn’t want to fall over neatly. It wants to form a C-shape bend in the mast with the belly of the C pointing away from the sideways pulling powerboat. See the image above.

Stopping that curve requires restraint at multiple heights—and on both sides of the mast.

So even some mid-level shrouds on the same side as the powerboat (the low side of the sailboat) quietly take load. Not huge loads—but enough to matter.

They’re not fighting the heel. They’re fighting mast curvature.

That realization was one of my favorite “ohhhhhh” moments of the day.

Putting Numbers (and Multipliers) to the Story

Here’s how the same 18° heel plays out numerically.

| Item | Masthead pull (3,000 lb @ masthead) | Wind load (same moment; 7,500 lb @ CE=30 ft) |

|---|---|---|

| Total sideways force to be reacted | 3,000 lb | 7,500 lb |

| Top level share (% / lb) | 45% / 1,350 lb | 25% / 1,875 lb |

| Mid level share (% / lb) | 35% / 1,050 lb | 45% / 3,375 lb |

| Low level share (% / lb) | 20% / 600 lb | 30% / 2,250 lb |

| Top multiplier → est. top stay tension | 5.85 × 1,350 = 7,900 lb | 5.85 × 1,875 = 11,000 lb |

| Mid multiplier → est. mid stay tension | 3.97 × 1,050 = 4,170 lb | 3.97 × 3,375 = 13,400 lb |

| Low multiplier → est. low stay tension | 1.95 × 600 = 1,170 lb | 1.95 × 2,250 = 4,390 lb |

The multiplier is the “door hinge penalty” — how much extra tension is required because the shroud angle isn’t perpendicular. Spreaders reduce this penalty.

Key takeaway: The wind uses more total force to get the same heel angle. The mast head pull on a rig with spreaders and lower shrouds helps share the mast head pull load and can lead to less or similar force in the top shroud than the wind load.

What the percentages show

-

Masthead pull concentrates load up high (more top-share) on a smaller load.

-

Wind pushes load into the middle and lower rig (more mid/low-share), even though the total sideways force is higher.

- The balance of different sharing and forces required makes our situation not so scary after all – wind loading requires higher force on the shrouds for similar heel.

Same heel. Different forces. Different force sharing.

The Real Drama: One Shot Only

What added to the tension that day was this simple fact:

This was it.

The highest tide. The only realistic window. Miss it, and we’d be waiting until the next king tide—days away—burning time, weather windows, and patience.

The plan was solid. Nature just decided to add a little extra mud for character.

Lessons from the Owner (and the Engineer Brain)

A few takeaways worth sharing:

- Always invest in your rig. Standing rigging isn’t the place to economize. Spreaders, shrouds, terminals—they’re not just hardware, they’re load-management systems.

- Use stretchy docklines for masthead pulls. We used a 3/4″ dockline, and that stretch mattered. Shock loads are the real killers. Even a small wave can create load multipliers that dwarf steady-state forces.

- Smooth beats strong. Every time. No snatch loads. No jerks. Just steady pressure.

And finally…

Next time I say, “The wind does this all the time,” I’ll probably add:

“…but the wind has better manners and a much longer attention span.”

Fair winds—and may your engineering brain only wake up after you’re safely tied to the dock.