Sailboat Gear and Throttle Controls

Throughout this course, and when maneuvering under power, we talk about shifting gears, throttle control, and RPMs. Below we cover the basics, including some helpful tips for mastering each.

Sailboats, and boats in general, use their gears and throttle to control momentum. It’s unlike driving a car in that you have no brakes! Instead, you use your forward and reverse gears and throttle to both increase and decrease speed.

A simple example: if you’re moving forward and want to slow down, then you shift into Reverse and apply the amount of throttle needed to slow down. And vice versa when in reverse, you shift into Forward to slow down your reverse speed.

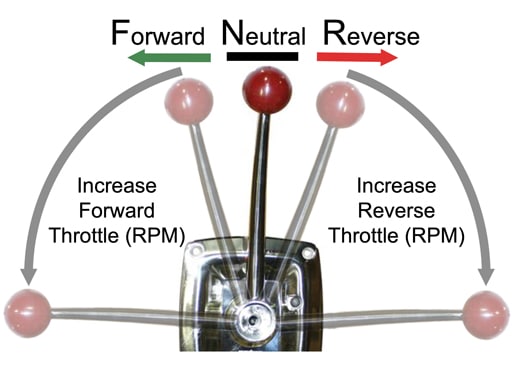

Below’s a diagram of a typical single, combination, gear, and throttle control lever. The middle is Neutral (you’re just idling with no forward or reverse), and then you can push it forward or pull it backward for Forward or Reverse gears. Since it combines the throttle, then pushing it MORE in one direction gives you more power (thus speed) in that direction.

*NOTE: many sailboats have separate gear and throttle levers, in which case think of the below diagram as 2 levers (one for gear and another for throttle).

Mastering Your Gears

Always ensure the engine is at idle speed before shifting from neutral to forward or reverse and vice versa. Abrupt gear changes at high speeds can damage the transmission.

- Pause briefly in neutral before shifting to allow the engine to adjust.

- Shift gears decisively when shifting from neutral to forward or reverse, and if you shift too slowly the gears may grind.

Mastering Your Throttle

Mastering the throttle on a sailboat enhances your overall control and safety on the water. It requires a combination of smooth, deliberate movements, coordination with steering, and a keen awareness of your surroundings.

- Practice Makes Perfect: Spend time practicing throttle control in various conditions. The more familiar you are with your boat’s throttle response, the more confident you’ll be in different situations.

- Neutral Position: Use the neutral position effectively to pause and reassess your situation without shutting off the engine. This is particularly useful when you need to stop momentarily to avoid obstacles or during precise maneuvers.

- Smooth Acceleration and Deceleration: Avoid sudden jerks when moving the throttle. Smooth acceleration and deceleration prevent unnecessary strain on the engine and provide better control over the boat. Gradually increase or decrease the throttle to maintain stability.

- Short Bursts of Power: In tight spaces or during docking, use short bursts of power instead of continuous throttle. This technique provides better control and allows for fine adjustments to the boat’s position.

- Maintaining a Steady Speed: When cruising, find the throttle position that allows the engine to run smoothly and efficiently. This not only conserves fuel but also reduces engine wear. Listen to the engine’s sound – a steady hum indicates optimal performance.

- Docking and Mooring: Precise throttle control is crucial when docking or mooring. Approach at slow speeds (i.e., “Slow is Pro”) and make small adjustments to position the boat correctly. Use short bursts of throttle rather than continuous power to maneuver into place.

- Handling Rough Conditions: In rough conditions, use the throttle to maintain control and stability. Increase power to navigate through waves and reduce it when cresting. This technique, known as “throttling,” helps manage the boat’s momentum and reduces the impact of waves.

RPM for Manuevering Under Power

Understanding and effectively using RPM (Revolutions Per Minute) is crucial when operating a sailboat under power. Proper RPM management ensures efficient engine performance, fuel conservation, and smooth maneuvering.

What is RPM?

RPM measures the number of revolutions the engine’s crankshaft makes per minute. It is an indicator of engine speed and is directly related to the boat’s speed and power output. Higher RPM generally means higher speed and power, while lower RPM indicates slower speeds and reduced power.

When it comes to throttle, you have one primary gauge that tells you the engine output: your Tachometer! Your tachometer is typically a circular gauge (like on your car) that displays RPMs in thousands, such as 0 to 5000 RPMs. Simply, More RPM = More Power = Sailboat Goes Faster (within limits).

RPM Key Considerations:

- Engine Specifications: Know your engine’s specifications – including the recommended RPM ranges for different operations – because each engine is different! This information is typically found in the engine manual and is crucial for optimal performance.

- Fuel Efficiency: Operating at the correct RPM can maximize fuel efficiency.

- Engine Load: The load on the engine varies with different conditions, such as wind, current, and sea state. Adjusting RPM according to these factors helps maintain a balance between power and efficiency.

Practical RPM Guidelines:

Check your engine specifications for the proper RPM ranges and limits for your engine and boat. These are just general guidelines, and engine specifications can vary!

- Idle Speed (600-1000 RPM): Use idle speed when the boat is stationary or maneuvering in very tight spaces. This low RPM range provides minimal thrust and allows for precise control during docking or when picking up a mooring.

- Cruising Speed (1500-2500 RPM): For most sailboats, the optimal cruising RPM range is between 1500 and 2500 RPM. This range balances speed and fuel efficiency, allowing for smooth and economical cruising. Always refer to your engine manual for the exact cruising RPM range recommended for your engine.

- Full Throttle (3000-4000 RPM): Use full throttle sparingly, typically only in emergency situations or when needing maximum power, such as against strong currents or high winds. Prolonged operation at full throttle can lead to excessive engine wear and increased fuel consumption.

- Avoiding Overloading: Avoid running the engine at low RPM for extended periods under heavy load, such as when motoring into strong winds or currents. This practice, known as “lugging,” can strain the engine. Instead, increase RPM to match the load demands.