Sailing Directions

Directions are super important because while sailing, you will always be in communication with others regarding directions of obstacles, wind changes, your destination, water current, and other boat traffic. Directions are stated in many ways, and so it is important to not only understand them but to communicate them to others in the proper manner. The terminology is important to learn now or else you’ll be ultra-confused on the boat when others are communicating to you – or them to you.

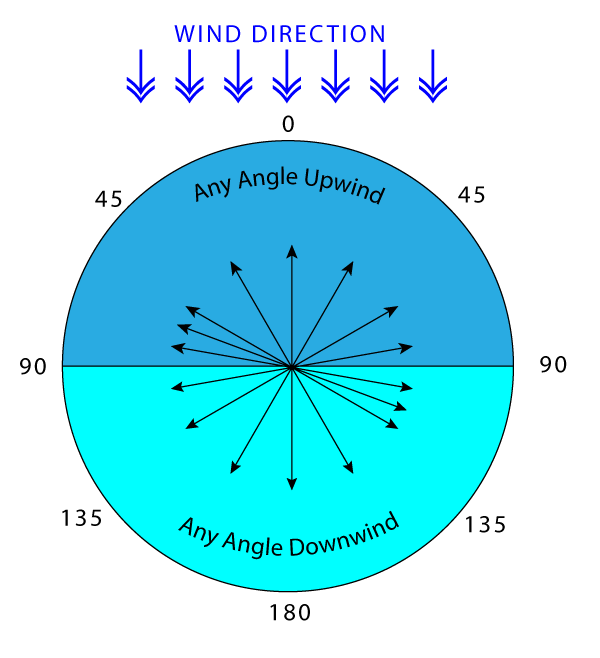

Upwind and Downwind

You’ll see and hear the terms “upwind” and “downwind” a lot and some confusion can set in.

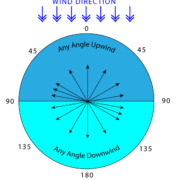

The term “upwind” can mean ANY direction that is toward the direction that the wind comes from. It does not have to be directly into the wind. Thus, 45 degrees upwind means 45 degrees off from where the wind is coming from. “Downwind” can mean ANY direction that is toward where the wind is going. Thus,135 degrees downwind means 135 degrees off from where the wind is coming (and it is toward a downwind position). 180 degrees downwind is directly downwind.

Angles to the wind are stated as zero through 180 (many times the word “degrees” will be omitted). Zero is into the wind directly. 180 is directly downwind. Any angle less than 90 degrees is “sailing upwind.” Any angle that is greater than 90 is “sailing downwind.” There is no angle greater than 180 in this form.

Upwind Downwind

Heading Up and Bearing Away

- Heading up or coming up means turning the boat more toward an upwind direction

- Heading up DOES NOT mean turning directly into the wind

- Bearing away or coming down means turning the boat more toward a downwind direction

- Bearing away DOES NOT mean turning to go directly downwind

Thus, a skipper may say “I’m bearing away to 135 degrees downwind angle” or “I’m bearing away to 135 degrees off the wind.” This would mean that the skipper is turning the boat so that it is sailing downwind 135 degrees away from where the wind is coming.

Head-to-Wind

Head-to-wind is a direction directly into the wind.

Luffing

When the boat is headed too far into the wind for the set of the sail, sails will start to flap at the leading edge (the luff edge of the sail). This is called luffing. When you are head-to-wind, the sails will be flapping wildly like a sheet on a clothesline. To fix this, bear away to fill the sail. If the sails are set too loose for the wind angle to the boat, a tactician might say “Bear away, you are luffing” meaning turn more downwind. Or the skipper might say “Come in on the mainsheet, the main is luffing” meaning to tighten the sails more toward the centerline of the boat (more on that in the sail trim section).

Luff-Up

Luff-Up means to bring the boat head-to-wind. Consequently, the sails will luff. A crew member might ask the skipper to luff up so that a tangle in the jib sheet may be released. Or a tactician might ask the helmsperson to luff up to slow the boat before a race starts to gain an advantageous position.

Now you know what this means: “You luffed up head to wind. Your sails are luffing. Bear away to 40 degrees to starboard off the wind.”

Port and Starboard

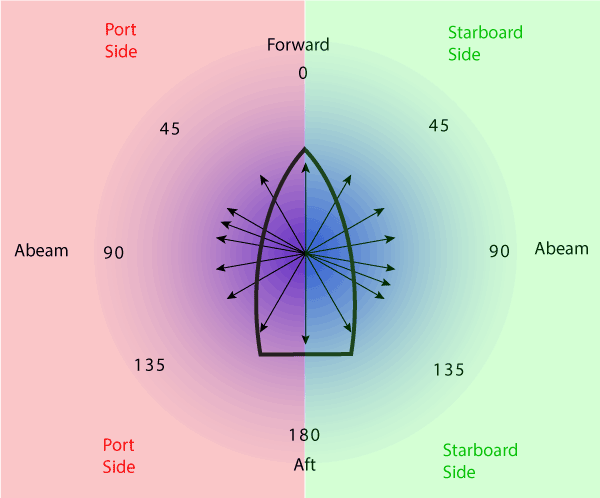

When facing forward, the port side is on the left and the starboard side is on the right.

If you look at the front of any boat, you will see a red light on the port side and a green light on the starboard side. These colors are by convention and are the same on every boat in the world. To remember this, use the mnemonic:

“Is there any red port left?”

Besides the reference to delicious after-dinner drinks from Portugal—the country whose sailors invented world discovery—the phrase reminds us that red is on the port side and the port side is on the left.

Angles Relative to the Boat

Relative Angles

Often angle directions are given relative to the boat. Zero degrees is always toward the front of the boat. A skipper might say “Watch out for that rock 60 degrees off our port side.” In this case, the direction has nothing to do with the wind direction. It means that if you are looking forward toward the front of the boat and then turn left 60 degrees you will see the rock.

The tactician might say “Come up 10 degrees.” This means relative to the boat heading now, turn the boat in an upwind direction 10 degrees. “Bear away 30” would mean turning the boat 30 degrees downwind from where it is now but keeping the wind on the same side of the boat (that is, no tack or gybe for this). To get a feel for these degree changes just think about how 90 degrees would be off your shoulders when looking straight forward—30 degrees is 1/3 of that. See the clock positions below.

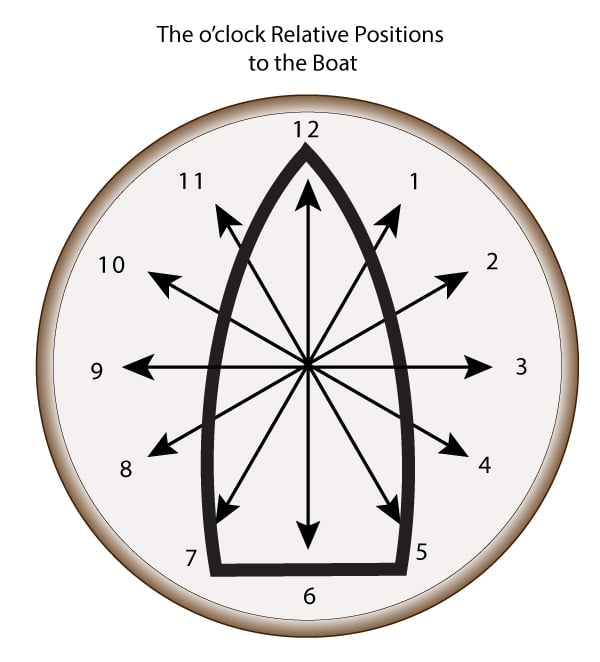

Relative to the Clock

To make directional changes when steering the boat, ALWAYS pick a spot on land or something (a cloud, a boat, a buoy) that is approximately where the direction change is to be. Then after you have picked it, make your change toward that or relative to that. Otherwise, you will begin your turn and not accurately know where to stop turning. Getting your direction changes wrong is a good way to get the helm taken from you by someone more competent.

In addition, a tactician may give you an angle in an o’clock manner. For example, “Do you see that boat at 3 o’clock?” These angles are also always stated relative to the front of the boat no matter what direction you are headed, with 12 o’clock being the front of the boat (bow) and 6 o’clock being the back (stern) of the boat.

While pretty obvious to most, the above is a graphic for the benefit of those brought up in the digital age only.

The o’clock description of directions is highly convenient and often used. There is no need to state port or starboard and for most of us, it is intuitive

In all other cases, angles and directions are given with the label distinction “upwind” or “downwind” OR “port” or “starboard” so that you can distinguish if the angle is measured from where the wind is coming from or relative to the boat.

These are examples of valid angle commands or observations using port or starboard relative to the boat.

- “Turn 90 degrees to port.”

- “A boat is at 130 degrees on our port.”

- “A rock is abeam to starboard” (abeam is 90 degrees).

- “There is a buoy in the water at 1 o’clock 100 meters out.”

These are valid direction commands or observations using wind angles.

- “Come up to 30 degrees off the wind.”

- “Bear away to 120 degrees off the wind.”

- “There is a boat downwind of us.”

- “Tack and then bear away to 45 degrees off the wind.”

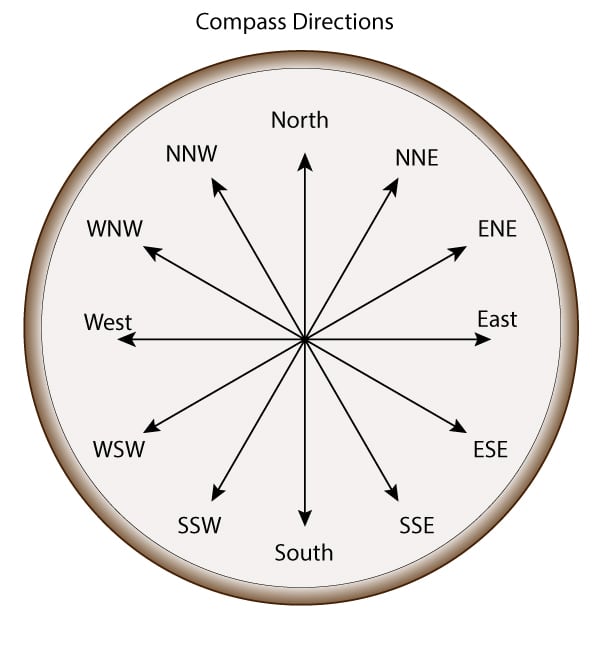

Compass Directions

Another set of directions used is compass directions. This is more fully covered in Chapter 9, Navigation.

A skipper may tell the helmsperson “Make your course 270 degrees on the compass.” This is referring to sailing the boat in a compass direction toward 270 degrees (270 degrees is west).

Compass directions are all about the compass and have nothing to do with the current boat heading, the wind, or the clock.

Relative to the Compass

Windward and Leeward

Windward refers to any direction toward the wind. Leeward (sometimes pronounced loo-ward) refers to any direction downwind. Thus, a lee shore is a shore that is downwind. The windward side of the boat is the side closer to where the wind is coming from. A boat to leeward means a boat that is in a more downwind position from you (though not necessarily directly downwind). Remember this from the Rules: a leeward boat is a stand-on vessel when both boats are on the same tack.

The High-Side and the Low-Side

When the boat heels over it creates a high-side to windward and a low-side to leeward. Typically the helmsperson sits on the high side of the boat to help balance the heeling force from the wind.

Highside – Windward side | Lowside – Leeward side

Many times the crew is placed “on the rail” (the high side) and told to think of fat thoughts of hot dogs and hamburgers to further counterbalance the heeling force.