Waves, Swells, and Depth

Waves, Photo Taken in Martinique

Since it is a good idea to keep your boat on top of the water, it’s good to understand the dynamics of water.

Waves

Waves are the product of wind blowing across the water.

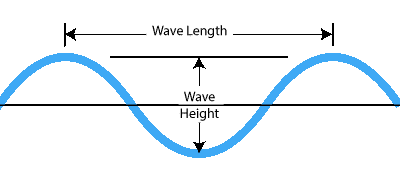

Wave Metrics

Wave height and wave length metrics are shown below. Another important metric is the period. The period of a wave is the time it takes for two consecutive crests to pass a stationary point. The frequency of the wave, although not used much in ocean wave metrics, is the number of waves to pass a stationary point in a certain amount of time. For example, 10 waves per minute is a measure of the frequency; the period then would be stated as 1 wave per 6 seconds.

Since waves are primarily the result of surface wind action, they can be accurately predicted. Waves have troughs and crests. Sailing in moderate seas is safe and easy, but as waves grow, their capacity for doing harm is greatly increased and requires expert sailing skills.

As waves get steeper and steeper their tops become tenably unstable. When propelled farther by the wind, the tops fall off, creating breaking waves. Take away the wind and the tops return to being stable but the waves themselves continue because there is nothing to stop them. This resultant wave is known as swell.

Swells

Swells are the result of waves from distant storms sometimes thousands of miles away. Their wavelength is long and generally, they are not a problem; with one exception: many sailors are subject to seasickness because of swells.

Depth

Sailors need to be a little more cautious than recreational powerboaters. To prevent being pushed sideways through the water by the wind, sailboats have a big long thingy sticking down from the bottom of the boat. It’s called a keel. For a medium-sized keelboat 26 feet to 52 feet (8m to 16m) or so, the depth of the keel will be around 4 to 7 feet (1.3—2.5 m). The “rudder,” which is the steering board thingy at the back, will be slightly shorter than the keel.

Keel and Rudder Depth

Depth sounders are reliable electronic instruments that determine the distance from the sounding transducer to the sea floor by using ultrasound pulses. These devices can be set to alert sailors when sailing close to shore, near atolls, or over other objects where you are uncertain about the water’s depth. Fishfinders can be incorporated with depth sounders, allowing sailors to also check for fish activity, should they wish to catch the “big one.”

Keep in mind that when sailing over areas that may have highly irregular bottom surfaces, such as coral, large rocks, and sunken objects, you may not have ample time to react to your depth sounder’s warnings. You must know where you are on the chart and be able to read the chart.

Harbors are notorious for having fluctuating depths due to currents and poorly scheduled dredging. Be wary of water depth any time you sail into a new harbor.

Depth Animation

In the olden days, they used marked lines attached to lead weights to determine depth. Nowadays, we use sonar signals traveling at the speed of sound to measure the depth (and to determine if there are fish around for dinner). Still, a prudent sailor will have on board a backup lead-weighted line. Recreationally speaking, it’s not practical to have a bowman calling out the depth of water every minute. Thus, almost every vessel these days has an electronic depth finder. Every experienced sailor will tell you that the cost of a depth finder is worth the investment. If your vessel does not have one, get one.

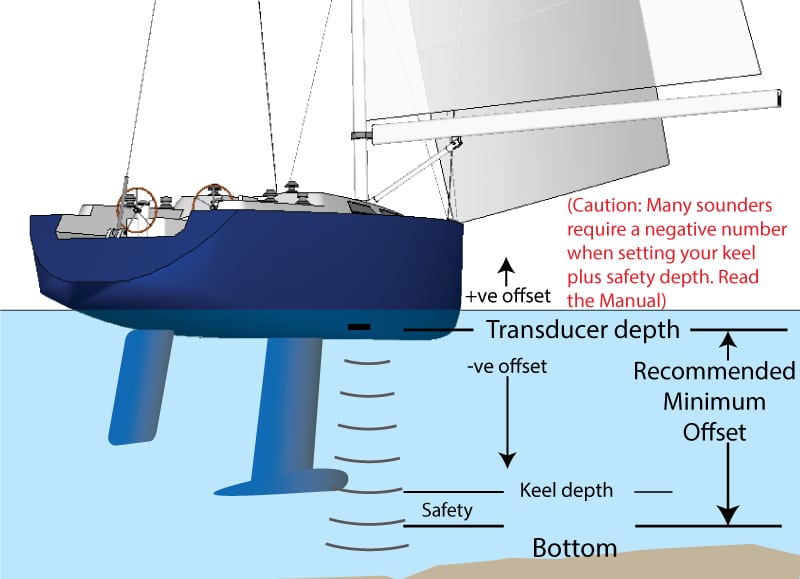

Offset

Depth sounders have a feature that allows the depth reading to account for the depth of the keel. For example, if your keel is 5 feet deep and the real water depth is 20 feet, you will have only 15 feet of clearance. Thus, you want the depth reading to show 15 feet. Caution however, when you set up your device—the offset number you need to put in is a negative number – err that is most of the time. You’ll need to read the manual of the individual device. Don’t assume a negative or positive offset when you set up the device. In the image below we assume a negative offset device.

Depth Offset

Tides

Tides are the regular rise and fall of the ocean due to gravitational forces from the moon and the sun. Tides vary in height all over the planet from zero to 50 feet (15 m), but for each specific location, they rise and fall a similar amount each cycle.

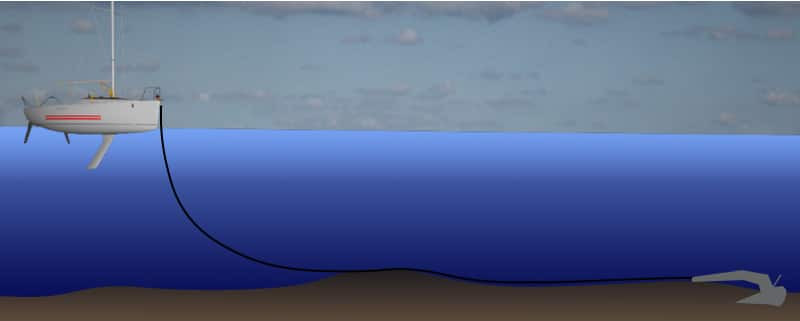

Be especially wary of tides when anchoring. Anchor at high tide, and you may find your boat resting on the bottom in a few hours. Anchor at low tide and you might find your boat drifting away in a few hours because the amount of anchor rode (anchor line) you put out did not account for the extra depth.

Fortunately, the depths listed on navigational charts are marked with the low tide depth. But this is not all you need to know about tides. Sailing is endlessly technical in its own nature. Further studies are always required.

Boat at Anchor

Current

Currents are the movement of water from one place to another. They can be consistently global in nature like the Gulf Stream which flows from the Gulf of Mexico, up the eastern coast of the USA and on to New Foundland then crossing the Atlantic Ocean where its name changes to the North Atlantic Current. Or ride the “EAC dude” with Nemo which flows from the Coral Sea down the east coast of Australia. All in all, there are many ocean currents that consistently flow in the same direction and travel over thousands of miles.

There are other local currents that are tidal in nature. Meaning that they flow according in direction and velocity to the tide. At high tide or low tide, the current is considered “slack” because as the tide gets ready to change the water velocity drops to near zero.

A Rough Ride

Sailing becomes less than idyllic as sea state conditions worsen. While waves and swell are due to wind there are some effects that can make them worse:

- Current: when current meets waves from different directions they create a confused heightened state of waves. Often, the waves become choppy and the wavelength is decreased.

- When swells meet waves: the superposition of these two can vastly increase the height and confusion of the sea.

- Distance from shore: when you have an offshore breeze the waves get larger in height the further from the shore.

- Depth of water: as water gets shallower wave height increases while also becoming steeper.

At the very North of New Zealand at Cape Reinga, two ocean currents meet — one from the Tasman Sea and the other from the Pacific Ocean. The waves seen here are the currents meeting in deep water – yet they are dangerously breaking. What if you were sailing using just your GPS at night?