Tacking and Gybing Maneuvers

Tacking

When you want to sail in a direction to exactly where the wind is coming from— guess what—you can’t! The best we can do is to follow a zig-zag course by sailing at about 30 to 40 degrees off the wind on one side for some distance then turning the boat to sail 30 to 40 degrees off the wind on the other side. Then repeat as necessary. With each tack, you turn the boat so that the bow goes through the point where the wind comes from. After the tack, since the wind is on the other side of the boat, the sails must also change sides of the boat.

Tacking to an Upwind Destination

Gybing

When you want to sail in a direction to exactly where the wind is going— guess what—you can! But . . . it has its difficulties because the sails must be held on opposite sides of the boat lest the mainsail “shadows” the headsail from the wind. They are thus balanced somewhat tenuously. Additionally, a direct downwind sailing direction reduces the wind speed that the sails “feel” by the boat’s own speed. – which reduces the speed of the boat. Sometimes you can reach your destination faster by turning off the dead downwind direction and sailing at a slight angle to the wind. You’re not heading directly for the downwind destination but the extra speed will make up for it.

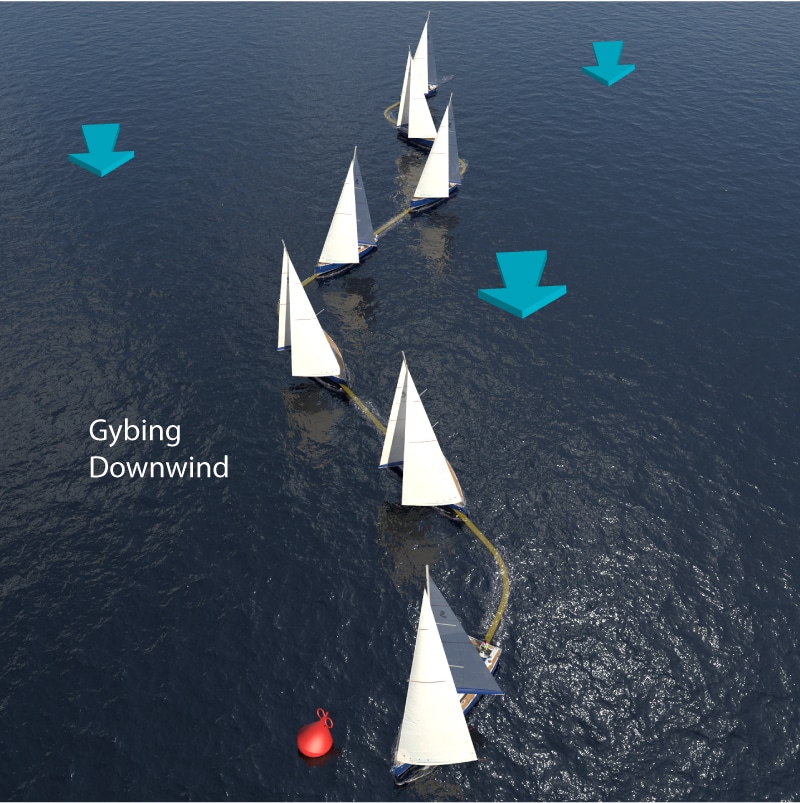

Gybing to a Downwind Destination

Often the headsail is lowered and a spinnaker or gennaker is deployed. We’ve all seen the gorgeous site of the big colorful and sometimes fun sail blowing out over the front of a boat as the boat sails downwind. These sails are either a gennaker or a spinnaker sail used exclusively for sailing in downwind directions.

Sailing Downwind with a Spinnaker

Usually, however, smart tacticians do not sail directly downwind even if that is the direction of their destination. From the Sail Trim course, you understood that the boat and thus the sails feel only the Sailing Downwind with a Spinnaker apparent wind. A smart tactician usually will “crack” off the downwind course a little and aim up at about 140 to 160 degrees maximum angle sailing downwind. By doing this, the boat picks up more apparent wind and thus boat speed than what it loses in angle when sailing directly downwind. Similar to tacking, the skipper must zig-zag the boat from one tack to another. But this time, since the maneuver means the boat is aiming downwind and the aft of the boat transverses the wind, the maneuver is called a gybe. Some people call it a jibe. Either way is correct. For consistency, we will use gybe.

Gybing is usually performed when you are sailing at an angle away from the wind, that is on a beam reach to a run. If you feel the wind on the back of your neck or around to the side of your face you will probably gybe the boat. This means turning the boat farther downwind, through the point where the wind is blowing, and then a bit more, so the wind is hitting you on the other side of the boat.

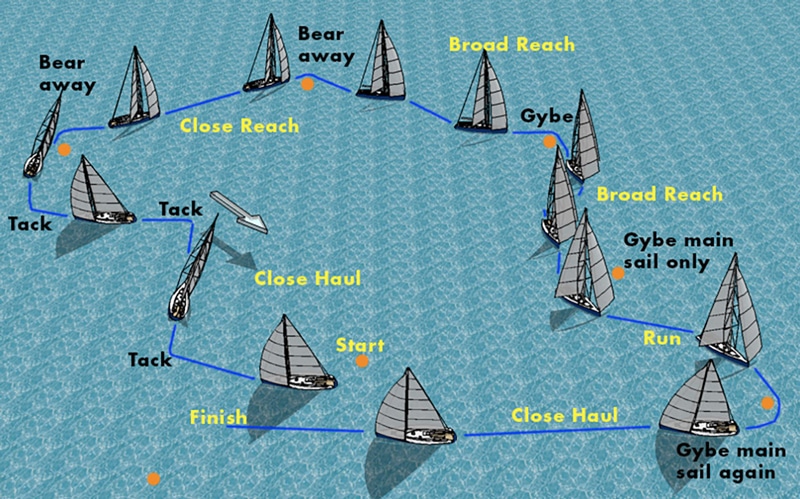

Tacking and Gybing

The following diagram shows a typical race course a skip- per must maneuver around. Careful study of this diagram will reveal all the secrets of sailing in one go. Notice the tacking and gybing maneuvers where the sails shift sides.

Sailing Maneuvers

The following is a video representation of the same sailing course.

Sailing Maneuvers Video

The below animation shows the distinction between a gybe over a tack. Whether you tack or gybe depends entirely on circumstances. Select carefully. Gybing has more potential for accidents, including equipment failures.

To perform either of these maneuvers efficiently, you will need to practice and get the “feel” of your vessel and establish rapport with it.

How to Tack the Boat

Alert the crew and passengers to this maneuver by announcing, “Prepare to tack.” or “Prepare to come about.” The crew begins by wrapping the non-working jib sheet (i.e. upwind sheet—also called the lazy sheet) 2 to 3 times clockwise around the upwind winch drum to prepare it for becoming the working jib sheet. Make sure the working jib sheet (about to become the lazy sheet) is ready to run clear.

The helmsperson then asks “Ready?” When the crew replies with “Ready,” the helmsman begins turning the vessel’s bow through the wind. There are a variety of nautical announcements that may be issued, the most common of which is “coming about,” but also heard are “helm’s alee,” “hard alee,” “tacking,” “helm’s over” or “lee ho.” All work just as effectively as you move the tiller or the wheel. The key is to have all the crew understand what is happening.

At the moment the headsail begins to fold in on itself at the forestay, the crew should ease the taut “working” headsail sheet, then unwind it off the winch completely, allowing the headsail sheet to easily run free. Watch and make sure this sheet does not catch on anything such as mast cleats or hatches.

An Expensive and Often Amateur MistakeA new and overly eager crew member wanted to winch in the jib sheet as we tacked. He neglected to chase the sheet with his eyes as he cranked (and cranked) while the jibsheet was caught under the hatch. $500 and a few weeks later we had a new hatch. |

As the headsail comes across the vessel’s foredeck, a crew member begins taking up slack on the other headsail sheet, previously prepared and wrapped loosely around the winch. Speed is of the essence here. The faster the crew member brings in the slack the less the crew member will have to use the winch to tighten the sheet when the load comes on. For this reason, it is a good idea for the helmsperson to tack slowly. Time spent tightening the sheet by the crew is time lost.

Trim both sails for the new point of sail, starting with the headsail first because the headsail controls the flow of wind (slot effect) over the mainsail. If you are tacking from one close haul to the other then there is little need to trim the mainsail. Concentrate instead on the headsail.

There is one refinement on the note above to tack slowly: An aside—when tacking, the vessel’s bow should be turned through the wind, fast enough to maintain forward momentum, but:

- If the rudder is turned too quickly, it will act as a brake and the boat may stall in low winds.

- Turning the rudder too quickly creates eddies in the water—not too much of a problem but it is energy you are taking out of the boat and giving to the water. Best leave the energy (that is, speed) in the boat.

- Turning the rudder too quickly gives the crew no time to properly get the headsail trimmed before the load comes on. This slows the boat.

- Turning the rudder too slowly may prevent the bow from completely coming through the wind. In this case, you may get stuck in irons or simply stall. You will need to turn back downwind, gain some speed, and try again.

Satellite Signature and Old HabitsI used to sail with an ex-submarine captain. He hated turning the boat too fast during a tack. When I asked him why, he muttered something about leaving eddies in the water that the Russians could see from the satellite. Old habits … |

When tacking from one close haul to another close haul on the other side of the wind, the boat will turn through about 90 degrees. This means that before you tack you should pick a point (a house, a tree, a landmass, a cloud, something) that you will end up sailing toward once you come out of the tack. “Ninety degrees?” you say. “How is that possible when a close haul is 30 degrees off the wind? It should be 60 degrees total for the tack? Aha, gotcha.” Sorry, you forgot the (approximate) 15 degrees between true and apparent. Thirty degrees apparent is really about 45 off the true: 45 plus 45 = 90.

Safety concerns: The jib sheets whip quite violently with the sail as the boat is pointing head to the wind. The new working sheet must be tightened as fast as possible to minimize this whipping, which can snap at crew members at speeds close to 100 miles an hour (160 km/hr). Anyone standing in the way of these whipping sheets can be severely hurt. If you think a whipping wet dish towel in the kitchen hurts then stay away from the jib sheets.

Tacking in VR

Here is a tacking maneuver, we filmed in Virtual Reality using the MarineVerse/NauticEd Virtual Reality Sailing App on Meta Quest. If you want to learn some good basics of sailing with Virtual Reality, take the NauticEd Virtual Reality Sailing Course.

How to Gybe the Boat

Gybing is one of the things that new sailors find slightly intimidating. Gybing is the act of changing sailing directions when you’re sailing downwind, so the stern of the sailboat passes through the wind, and one or more sails change sides. This is the functional opposite of tacking where the bow of the sailboat turns through the wind.

During the gybe procedure, the sails are switched to the other side of the sailboat automatically by the wind.

When proper precautions are taken. gybing is easy and safe. However potential problems can arise if the boom is permitted to swing rapidly and unrestrained from one side of the vessel to the other. This can be dangerous to crew and boats, so do it carefully.

The boom’s swinging can be violent during a gybe because the wind is blowing from the back end of the mainsail and once it gets on the other side of the mainsail the boom swings quickly across. (During a tack, the wind blows from the leading edge so this tends not to happen.) A chicken gybe, discussed later, is actually tacking instead of gybing to avoid the potential dangers of gybing when high winds exist.

The Gybe

To help visualize the dangers of gybing, imagine you are a mast and you attach a piece of plywood to your back so that it extends away perpendicular to your back. Now go outside on a really windy day. Imagine what happens as you turn your face through the point of origin of the wind. Nothing too violent as the plywood is being blown downwind through the turn. That’s a tack. Now keep turning around so that your back goes through the wind. When the wind catches the other side of the plywood you’ll probably be launched over so hard you’ll be glad this is only imagination. That’s a gybe! Ouch!

On top of all that, since you’re probably flying a headsail as well, you’ve got to deal with that at the same time. Left unattended during a gybe the headsail will first fly forward then come around on the wrong side (the downwind side) of the forestay. You’ll have a real problem trying to get it back into a sailing position as the boat straightens out on the other side of the wind. And for a new sailor trying to impress their crew, it’s totally embarrassing.

So here are the tricks to gybing that make it simple and easy on your sailboat rigging and crew.

- Begin by alerting the crew and announcing: “Prepare to gybe.”

- Ensure loose items below decks are stowed and drinks and gear above decks are secured.

- Check all around for traffic.

- Ensure no crew are in harm’s way of the swinging boom or lines changing over on the foredeck.

- Prepare the headsail by hauling in taught on the lazy headsail sheet (the upwind sheet that is not doing anything) and cleating it off around the winch. This will prevent the headsail from wrapping around the forestay during the maneuver and will place the sheet almost in position for fine-tuning after the gybe maneuver is complete.

- Prepare the mainsail by hauling in on the mainsheet bringing the mainsail toward the center of the sailboat. This will be relatively difficult since there is a lot of pressure on the mainsheet. As you become better at gybing and your crew becomes more finely tuned, you can begin turning the vessel and simultaneously haul in the mainsheet until it is amidships. Turning reduces the pressure on the mainsail and makes it easier to haul it. But take note that the timing has to be perfect. So, until you and your crew are finely honed at gybing, the best practice is to pull in the mainsail before you execute the turn. Bringing the mainsail close to the center of the sailboat prevents the boom from swinging through a large arc. This in turn prevents the boom from building up a great speed as it swings across. It’s the speed of the swing that causes the damage to the rig and crew.

Of biggest concern is the crew. If the boom is allowed to swing dangerously across at speed, the crew can be hit in the head quite possibly killed—it has happened. Many crew members had been slung overboard and drowned while unconscious. Take heed!

- Of secondary concern is SERIOUS damage to the gooseneck—the connection point of the boom to the mast—or other parts of the rig.

- The next trick is vital, or your sailboat will be violently heeled over and rounded up into the wind. As the boom flips across because the wind is now on the other side, QUICKLY ease the mainsail out to its desired position. If the mainsail is not eased fast enough, the center of pressure of the wind is aft on the rig as the boat completes the gybe. But aft COP pushes the stern of the boat downwind, which rounds the boat up into the wind. W2NW3 (Which Was NOT What Was Wanted).

The best way to do this is to appoint a crew member to manage the mainsail. Ensure they have the mainsheet wrapped around a winch (clockwise) with the clutch released or uncleated. As the boom flicks over to the other side, immediately release the mainsheet out in a controlled fashion.

- As the headsail is coming across, another crew member should now release the old working headsail sheet completely allowing the new leeward working headsail sheet to take the load.

- Now you have successfully gybed and the only matter is for the crew to observe the new heading of the vessel and trim both sails accordingly.

- Phew!

Gybing in VR

Here is a gybing maneuver, we filmed in Virtual Reality using the MarineVerse/NauticEd Virtual Reality Sailing App on Meta Quest.

The Accidental Gybe

The accidental gybe occurs when the helmsperson is not paying close attention. It is a rookie mistake that can cost dearly with injuries (death) and damage. You must avoid an accidental gybe.

When sailing directly downwind, a rookie helmsperson takes his eyes off the wind indicator and allows the boat to drift into a position where the wind is coming from the same side on which the mainsail and boom are positioned. This happens after a shift in wind or a slight course change. The wind, now on the other side of the sail, pushes it over quickly and with it the head-knocking high-speed killing boom. Bam!

If you are sailing at any angle close to downwind, you must keep a diligent eye on the wind angle and keep rookies off the helm or anyone who gets distracted easily.

Sailing by the Lee

Sailing by the lee means that the wind is coming from behind (you are sailing downwind) and anywhere from 0-30 degrees angle off to the same side as the mainsail.

Sailing by the lee is possible and done BUT it is very dangerous because you are extremely close to the accidental gybe position above. The reason you might do it is that it helps keep the head sail full when it is on the opposite side of the mainsail. Both sails get good exposure to the wind from behind without the mainsail shadowing the wind from reaching the head sail.

If the mainsail is let all the way out, the wind will still hold the mainsail out rather than swinging it over. But you are riding on the edge.

Sailing by the Lee should not be done in shifting wind conditions or large swells – as an accidental gybe will be very violent. Only an experienced helmsperson should be on the helm – the helmsperson must be on constant watch of the boom – and that helmsperson should automatically know that the moment the boom even thinks about moving, the helmsperson needs to immediately turn the helm wheel away from the boom side. In the case above, the helmsperson should steer to port – IMMEDIATELY – without thinking. This puts pressure back on the main sail to hold it in place.

When sailing by the lee, make sure a crew member is assigned to the main sheet and is ready to—at less than a moment’s notice—quickly haul in on the mainsheet to capture the boom before it SLAMS all the way across. Tell all crew members to keep their eyes up and their heads down. No one walks forward on the non-boom side – if an accitendat gybe happens the speed of the boom can easily kill – which has been known in many cases to do exactly that.

Hopefully, the above paragraphs accentuated the danger of Sailing by the Lee.

Gybe Preventers

Several devices and ideas work to either slow down the boom from accidentally gybing fast or to completely prevent the boom from moving.

This video from Yachting World is an excellent run-through of these devices and methods.

Yacht World Magazine Video

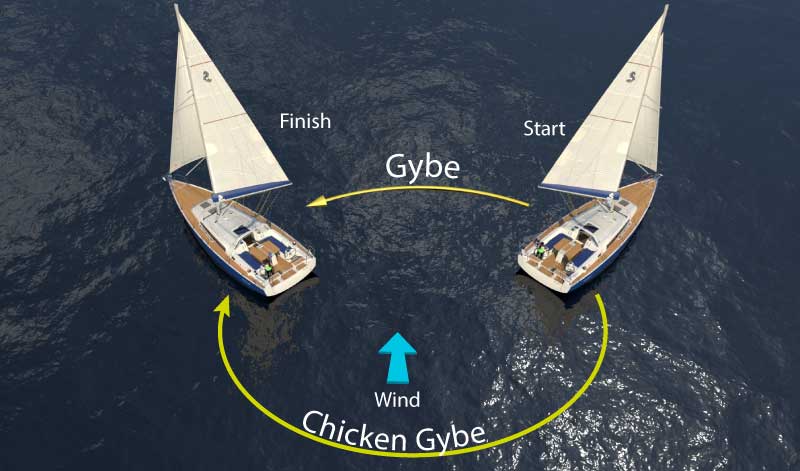

The Chicken Gybe

In high winds, 15 knots and above, we don’t recommend gybing. Instead, use the “chicken gybe,” which is essentially a 270-degree tack. Instead of turning the boat downwind, you turn the boat up into the wind and perform a normal tack then bear away from the wind to the desired point of sail.

Chicken Gybe

The chicken gybe is mostly performed when the skipper is uncomfortable because of high winds. The chicken gybe is much safer. And the end result is the same. You are merely tacking the boat from a broad reach on one side over to a broad reach on the other side. It’s simple, easy, effective, and safe. The only thing to watch out for is that the jib sheets will whip back and around quite violently. So, it’s a good idea not to have anyone near the jib sheets (that is, on the foredeck).

Here is an animation of the sails as they go through the gybe and chicken gybe maneuvers.

Gybe and Chicken Gybe

Here is another animation of the boat as it moves through the gybe and chicken gybe maneuvers. We had a little fun with this one.

Gybe and Chicken Gybe Maneuvers

Also in high winds, a gybe will tend to round the boat up into the wind very quickly and cause excessive heeling. This is usually upsetting to the crew. To prevent excessive heeling, once the mainsail gybes are over, you’ve got to let out the mainsheet as quickly as possible. Getting the mainsheet out will stop the rounding up and heeling over. Hence, before you go gybing in high winds, become an expert in lower wind conditions first and use the chicken gybe method until you’ve gained the confidence to gybe correctly every time.