Essential Information You Must Know

The Hidden Danger of AIS

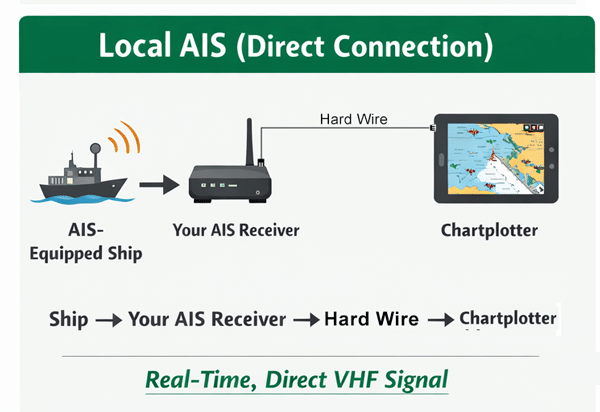

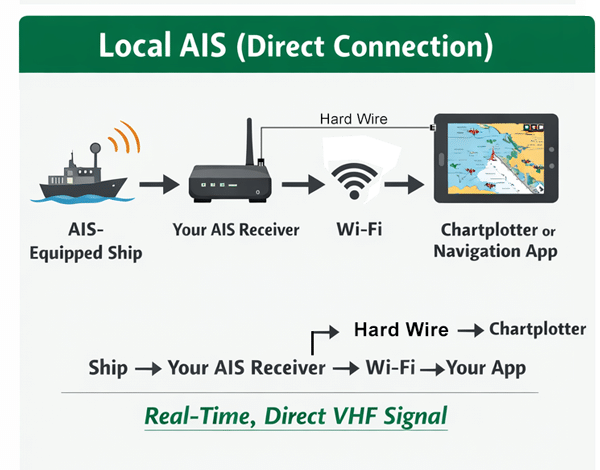

Quick takeaway: AIS on your chartplotter is direct VHF broadcast data — real-time and complete within range. AIS data in phone apps comes from internet aggregators and can be delayed, incomplete, or missing. Confusing the two systems can lead to dangerous decisions.

The Dangerous Assumption Boaters Make About AIS

AIS is one of the best safety tools we’ve ever added to modern boating. It’s also one of the most misunderstood, mostly because people think “AIS on my chartplotter” and “AIS on my phone” are the same thing. They can look identical on a screen, but they’re not the same system, and once you understand why, a lot of confusion (and a few dangerous assumptions) go away instantly.

I was reminded of this in a very practical way while sailing near Ibiza. We were doing a nighttime crossing from Ibiza to Mallorca — it was dark but with a clear starry sky, with busy recreational and commercial traffic moving through. I opened an internet-connected AIS app on my phone, expecting to use it as a secondary cross-check for collision avoidance. What happened next was uncomfortable: I could see commercial ships’ lights with my own eyes, but they weren’t showing on the app, or they showed up with positions that were obviously stale. On my Chartplotter, I could see them all. That moment didn’t make me distrust AIS; it made me trust AIS more—because it clarified what was actually failing. It wasn’t AIS. It was the internet version of AIS.

What AIS Is and How It Actually Works

To make sense of that, you have to start with what AIS really is. AIS—Automatic Identification System—is not an internet system. It’s a radio system. Ships broadcast short digital messages over VHF that include their identity, position, course, speed, and navigational status. Your AIS receiver listens to those broadcasts and displays what it hears. That’s the entire idea. The onboard data path is simple and direct: the other ship broadcasts, your receiver hears it, your chartplotter displays it. No cellular plan, no cloud services, no website, no third party. For collision avoidance, this is the “real” AIS system, and it’s exactly what AIS was designed to support.

The Difference Between Onboard AIS and Internet AIS

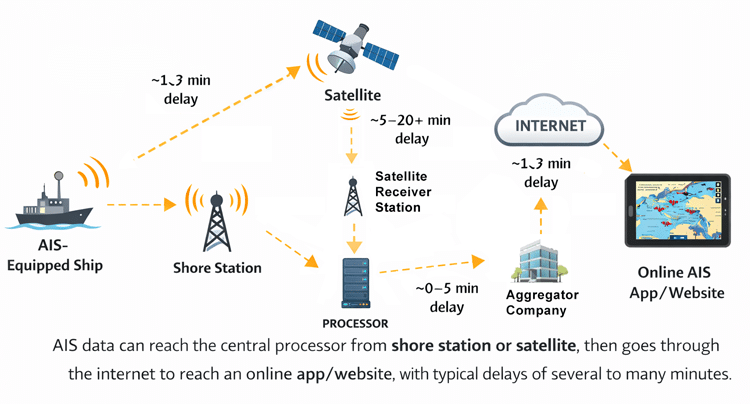

The confusion begins the moment AIS shows up online. AIS does not automatically live on the internet. For AIS targets to appear on a website or phone app, somebody else has to receive those VHF broadcasts—either a shore station near the coast or a satellite overhead—and forward that raw data into a private data system. The companies that do this are called AIS aggregators. MarineTraffic, VesselFinder, FleetMon, AISHub, and a few others gather AIS messages from thousands of receivers, combine them with satellite AIS feeds, clean and merge the data, and then publish their own live traffic maps through apps, websites, and APIs.

Here’s the important part that most people don’t realize: there is no single shared terrestrial AIS network. Each aggregator has its own receiver network and its own contracts. A shore station in one marina might feed MarineTraffic and not VesselFinder. Another might feed a different platform entirely, or a port authority might keep its data internal. So when you look at “AIS on the internet,” you are not looking at the same “ground truth” that your chartplotter is showing. You’re looking at whatever that aggregator’s network happens to collect at that moment, in that location, through that specific chain.

Why AIS Targets Can Disappear or Be Delayed

That’s exactly why the Ibiza situation played out the way it did. The ships I could see were clearly transmitting AIS, because in the real world commercial ships are broadcasting constantly, and a boat in VHF range with a proper receiver will generally see them. The reason they weren’t showing on the app wasn’t because AIS was failing—it was because the app’s internet data pipeline pathway from ship to satellite or ground station to processors to aggregators to internet to cellular to app wasn’t capturing the same reality. Either no public shore station was receiving those ships in that area, or the stations that did receive them weren’t feeding the aggregator behind my app, or the data was delayed and cached somewhere along the way. In other words, the problem was not the ship. The problem was the collection network and the publishing chain.

Once you see that clearly, it becomes obvious why internet AIS can never be used as a collision-avoidance tool. Onboard AIS updates in seconds and is complete within VHF range because you’re receiving the broadcast directly. Internet AIS is “best effort.” It can be delayed minutes to even hours, it can have gaps, it can drop messages in busy areas, and—most importantly—you generally don’t get a warning that a vessel is missing. The screen looks authoritative, but it’s not guaranteed to be complete, and you can’t safely maneuver a boat based on a map that might be missing the very target you most need to see.

This is why the safety rule I teach is simple: if AIS data is coming from the internet, it’s advisory only. It’s fine for planning—checking traffic patterns, seeing what’s anchored in a bay, watching a ferry route, or doing a little reconnaissance for a busy port. But it is not a navigation instrument and it should never be used for collision avoidance. That’s a job for onboard AIS, radar where available, and your own visual lookout and COLREGs judgment.

AIS Receiver To WIFI To App

Now, there is one important exception that people should know about, because it’s where tablets and apps actually can be completely legitimate. If your app is connected directly to your own onboard AIS receiver or transponder via Wi-Fi or a wired NMEA gateway, then the app is not using internet AIS at all. In that setup, the app is simply displaying the same raw AIS sentences your chartplotter would display. The data path is direct again: ship broadcasts on VHF, your AIS receiver hears it, and your app displays it locally. Architecturally, that’s equivalent to a chartplotter. The practical risks are different—Wi-Fi can drop, tablets can sleep, batteries can die—but the underlying AIS information is the same real-time local radio data.

Shore Station Networks Don’t Report to All Aggregators

A related question I get all the time is why different AIS websites don’t agree with each other. It’s because of how those shore stations work. Many are volunteer stations, some are ports, some are universities, some are private installations. They choose who they feed, and many feed only one service because it’s simpler, or because there are contractual reasons. So each aggregator ends up with a slightly different global view. That’s also why you can be near land and still see inconsistent online AIS—coverage is not just a geography problem, it’s a network membership problem.

People also ask about government AIS, especially in the U.S. The Coast Guard operates NAIS, the Nationwide Automatic Identification System, and it is a serious, high-reliability network used for vessel traffic, search and rescue, law enforcement, and security. But it is not a public website. There is no “NAIS traffic map” you can pull up as a recreational boater, and that’s intentional. Commercial AIS websites are not official traffic services; they are privately operated aggregators publishing their own best-effort view of the world.

One final technical note helps explain why big ships show up everywhere while yachts sometimes vanish offshore. Commercial ships typically transmit Class A AIS at higher power, which satellites detect far more reliably. Most yachts transmit Class B at lower power, and satellite reception becomes intermittent and “bursty.” That’s why offshore tracking for smaller boats can look like a dotted line—updates arrive in chunks, not continuously. Again, that’s not software. It’s physics, power, and decoding limits.

Safety Vs Tracking

So here’s the mental model I want every student to carry forward: onboard AIS is a safety system. Internet AIS is a tracking system. They can look the same, but they behave differently, and competent boaters never confuse them. Ibiza didn’t teach me that AIS is unreliable. It confirmed something more useful: AIS is extremely reliable—as long as you stay inside the system it was designed to be. The moment you move AIS into the internet, you’re no longer navigating with live local radio data. You’re observing a partial, delayed reconstruction of that data. And once you see that clearly, you’ll use each tool for what it’s good at—and you’ll be much safer for it.

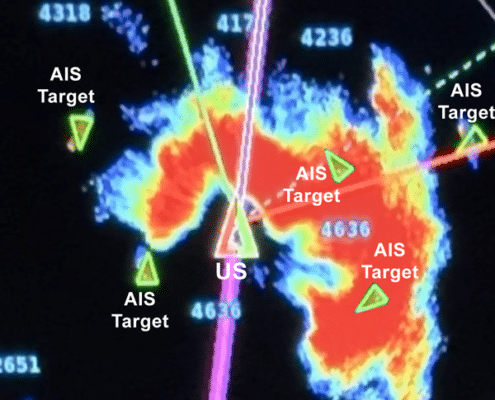

Radar and AIS

One of my favorite real-world reminders that chartplotter AIS and radar are complementary—not redundant—comes from the moment shown in the chartplotter radar/AIS overlay image here as we were entering a heavy rain cell at night off the coast of Honduras on the way to Livingston, Guatemala. The big red and yellow mass on the display is radar-reported rain clutter: marine radar operates in the microwave bands (typically X-band around 9 GHz or S-band around 3 GHz), and precipitation is very good at reflecting and scattering microwave energy. That’s why the storm lights up the screen and why radar-identified targets inside or behind heavy rain can become difficult to separate from the clutter. AIS, on the other hand, is VHF radio (around 162 MHz), and rain simply doesn’t attenuate VHF in any meaningful way for normal marine ranges. So even when the radar picture is messy, the AIS targets still show cleanly right through the rain area—identity, course, speed, the whole story. In conditions like this, radar is still valuable, but AIS often becomes the more reliable way to confirm what’s out there and how it’s moving, because weather degrades radar far more than it ever degrades VHF AIS.

However, we must constantly remind oursleves that not all vessels are broadcasting AIS. In the limited visual situation (heavy rain plus nighttime) shown in the image, there is still extreme danger.

You can learn more with the Electronic Navigation Course

Stop guessing. Start navigating with intent.

Most sailors know how to pan and zoom a chartplotter. Very few know how to use AIS, radar, CPA/TCPA, and manage the system settings to actually avoid collisions and groundings and manage risk. Whether is using a chartplotter or an App, NauticEd’s Electronic Navigation Course shows you how modern navigation systems work together — and how to use them properly when it matters most.